"Human rights" is a broad term, and some people's (and companies') interpretation is broad beyond belief. Here's a very effective technique for analyzing claims of human rights violations: ask yourself with what more specific word the first part--"human"--could be (more) appropriately replaced in the given context.

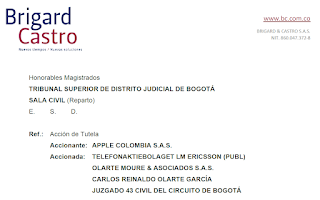

Yesterday it became public in Colombia that Apple is--I kid you not--claiming a human rights violation and invoking Article 8 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights because of Ericsson's preliminary injunction in Colombia over a 5G patent. Nowhere on the 48 pages of the motion did I find a human rights violation in the sense in which most reasonable people would understand it. All I found was a bunch of run-of-the-mill appellate arguments. The more appropriate term is "defendants' rights in commercial litigation." Arguably, we're talking about patent infringers' rights--and the problem is then that patent holders' rights are really a constitutional matter (property). Whether or not Apple actually will be deemed an infringer when all is said and done, the proper procedural avenue for that is a (regular) appeal.

Interestingly, Apple has just been warned against being sanctioned by the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Texas over a "misuse" of court rules. They brought an emergency motion instead of a regular motion.

When I ran a Twitter search for Apple in connection with human rights, one of the first tweets that came up linked to a Wired article, The Fallout from Apple's Bizarre, Dogged Union-Busting Campaign." The tweet talked about "the depths that #Apple will sink to in order to deny their workers basic human rights." (emphasis added)

Here again, the question is whether we're talking about human rights in a narrow sense or, more specifically, workers' rights. The freedom of association, which enables employees to form and join unions, is the latter. What happened at some of Apple's suppliers may be a different story, but as long as we're just talking about union-busting, I'd call it an attack on workers' rights--which is bad enough (don't get me wrong).

Now let's talk about developers' rights. Apple is taking its disdain for developers' rights to a new level now by expanding its Search ads--after wreaking havoc to businesses and entire business models, and potentially contributing to a recession as a venture investor noted--to individual apps' App Store pages.

They're now adding insult to injury. It means that app developers who already invest in development and marketing to get potential downloaders to visit their App Store page--where they're one click away from what you want them to do, which is to download your app--may have to pay off the big gatekeeper bully again or their competitors will redirect that precious traffic on the final screen on which you're vulnerable to competitors' ads.

Tim Sweeney, the CEO of Epic Games, accurately says "Apple will litter your own app page with ads for competing apps" (after already running Search Ads before people even get there)--and he's right that "Apple must be stopped":

They front-run searches for your trademarked app name, and place ad results above the result for your app.

— Tim Sweeney (@TimSweeneyEpic) July 29, 2022

But now, there’s more: Apple will litter your own app page with ads for competing apps. And keep all the ad money for themselves.

Apple must be stopped.

What's the solution? It's not impossible--but won't work in every jurisdiction--to combat this kind of abuse under existing laws. New digital platform laws such as the EU's Digital Markets Act may provide a fundamentally better basis, but won't necessarily close each loophole either, at least not immediately. However, what the DMA allows is bypassing Apple's App Store through direct installations and alternative app stores. That could help indirectly. If Apple faced competition from third-party app stores, Apple as well as its competitors would have an incentive to treat developers better. In the absence of such competition, you have the Kodak/Newcal situation of a single-brand market: while the iPhones competes with Android devices in the smartphone or smartphone operating system foremarket, there's no competitive constraint in the aftermarket of iOS app distribution because Apple can do almost anything it wants to app developers--even violate developers' human rights as long as there's no outcry in mass media--without losing any market share in the foremarket.

Lawmakers, regulators, and courts can see that Apple is shamelessly exploiting its monopoly power in the aftermarket by taxing app developers, massively diminishing a key revenue source for developers (in-app ads, at least until Apple introduce its own system), and further increasing user acquisition costs, which in part means money in Apple's pockets (example: app developers paying for ads related to their own app and place them on individual apps' pages just to reduce the likelihood that someone else's ad will appear on their own App Store page). The worst-case scenario would be that Apple places ads for its own apps on competing app developers' App Store pages--Sherlocking on Apple Search steroids.

Apple is unrepentant. Class action after class action gets filed. Antitrust investigation after antitrust investigation gets launched. But lawmakers and regulators must act more swiftly and more decisively, lest this end up like The Tortoise and the Hare. It was a major mistake--though easily explained against the political backdrop--that too many politicians and regulators initially let Apple get away with its "privacy" pretext.