The Epic Games v. Apple appellate hearing in San Francisco--with the DOJ supporting Epic's appeal--is less than four weeks away. With all that's going on (including my own new app project) I don't know yet how much time I will find in the coming weeks to elaborate on additional aspects of the case, but at minimum I'm now going to complete my analysis of the market definition dispute. I've done a lot of reading in recent days on the subject of single-brand markets, and I've drawn up a half-dozen charts that will make it easier to follow.

In order for Epic to convince the United States Court of Appeals for the Nith Circuit of its single-brand market definition under the Supreme Court's Kodak precedent, it has to proffer a (competitive) foremarket and a (monopolized) aftermarket. Then the focus is on whether Apple abuse its aftermarket monopoly.

I've previously explained in detail why Judge Yvonne Gonzalez Rogers of the United States District Court for the Northern District of California got the law, the economics, and the technology wrong with respect to the foremarket part. I realized the full extent of the judge's fundamental misconceptions only after identifying outrageous absurdities such as the judge

saying that Epic chose the smartphone operating system market because Apple has a greater market share in that one than in the smartphone market (when there is no iPhone without iOS, and the iPhone is the only smartphone running iOS, i.e., a one-to-one relationship), and

referring to multiple App Store operating systems, when there is just one (iOS).

It was Apple's own admission that iOS does compete with Android (which reduces to absurdity its denial of the existence of a smartphone OS market) that pointed me to this in the first place.

What the Supreme Court held in Kodak 30 years ago is that if certain criteria are fulfilled, there are exceptions to the general rule that a market is characterized by more than one vendor offering products (which includes services) that have the potential to substitute each other. The most important one of those requirements is also the only one that matters here (as Judge YGR didn't see any issues with the other three): that competition in the foremarket fails to discipline a defendant's conduct in the aftermarket.

The Supreme Court didn't resolve the case after a full trial: it merely held that the complaint should survive a motion to dismiss in light of plausible factual allegations according to which Kodak enjoyed market power in the aftermarket of spare parts for its high-volume photocopiers despite having to compete with other makers of photocopiers in the foremarket. In other words, if the allegations were taken as true, Kodak could--with impunity--act anticompetitively in the aftermarket without customers defecting in the foremarket or competitors seizing an opportunity to undercut Kodak on the total cost of ownership (TCO), such as by adopting a similar razor-and-blades type of business model and slashing photocopier prices, which would serve as a competitive constraint on Kodak.

That is merely consistent with what characterizes market power: it's a state of affairs in which a monopolist can make certain decisions (such as price increases or degradations of quality) without having to worry too much about competitive constraints. That's what the SSNIP test (Small but Significant Non-transitory Increase in Price)--as in Epic v. Apple--and its SSNDQ equivalent (Small but Significant Non-transitory Decrease in Quality)--as in the EU's Google Android case--are all about. So Kodak says that the question of whether an aftermarket is a relevant antitrust market hinges on whether there are competitive constraints by virtue of competition in the foremarket. If there are, that's good. If not, then the markets are dissociated, and there may be an issue in the monopolized aftermarket. Here's my first chart (click on the image to enlarge):

As simple as it may seem, this chart visualizes something that is easily misunderstood. The notion of competition in the foremarket disciplining an actor in the aftermarket presupposes a feedback mechanism. There must be a price for the actor to pay in the foremarket if it raises prices (such as by driving out competitors in order to command higher service prices) in the aftermarket. That price may be paid as a result of reduced demand (TCO-savvy customers buying from competitors) or pressures on the pricing of the original equipment (as other vendors give them away below marginal cost as they look at lifecycle revenues that include the aftermarket). All that matters in the end is that there is such a feedback mechanism. In that case, some customers may still feel they are treated unfairly, but the damage (also called deadweight loss) is limited, and therefore not worthy of antitrust intervention.

So, whoever says that competition the foremarket disciplines decisions in the aftermarket implicitly means that installed-base opportunism in the aftermarket will be a boomerang that hits--and really hurts--the actor in the foremarket.

Here's a chart that shows Epic's proposed market definition--one foremarket, two aftermarkets (click on the image to enlarge):

In this chart and in a few others, the dotted line is labeled "singularity"--a key point in evolution--because I want to stress how important that point is: it's the transition from a competitive market to a world of monopolies. Once you're past that threshold, there may also be a second-degree aftermarket (here, IAP) or even nth-degree aftermarkets. But the critical point is where actions to the right don't have consequences to the left of the dotted line anymore. Thereafter, it's game over for competition.

Epic said that iOS does compete with Android, as Apple has meanwhile admitted, but it can abuse its App Store monopoly in really bad ways without losing market share in smartphone operating systems (or at least not to an extent that would discourage Apple).

Unfortunately, Judge Rogers misunderstood Epic and thought that Epic chose the smartphone OS rather than smartphone (device) market in order to describe iOS as a monpoly, i.e., that the antitrust theory begins with Apple not allowing other operating systems on the iPhone than iOS (click on the image to enlarge):

As a result of that misconception, she moved the singularity to the left.

She then rejected the foremarket. As iOS isn't sold or licensed separately, she said there could not be a market for something that isn't sold. The DOJ disagrees sharply, as do other amici. This plays a role in this case in a second way: Apple's in-app payment service is not offered outside the App Store (though other payment services, like Paypal or Stripe, obviously are).

I can't imagine that anyone reviewing that fundamentally flawed part of the judgment would not be inclined to reverse Judge YGR with respect to the foremarket. But Epic also needs to prevail on the aftermarket.

As I said further above, the focus must be on the singularity: the line between the foremarket and the first derivative aftermarket. So let's simplify the chart accordingly as things will get a bit more complex in a moment (click on the image to enlarge):

Building on the previous chart, let's now look at why this is a Kodak case, i.e., why Apple can get away with terrible actions in the aftermarket without paying a dissuasive price in the foremarket (click on the image) to enlarge):

First, on the left side of the above chart you can see that the foremarket is a duopoly (which I sometimes call "Goopple"). This is not like the photocopier market where you have dozens of vendors, and there are plenty of companies who could enter the market if they so elected. It's a network effects-driven market where even Microsoft's Windows Phone didn't stand a chance at some point as developers were writing their apps only for iOS and Android.

If Google wasn't only marginally more open than Apple ("fauxpen"), but decided to turn true openness into a competitive advantage, smartphone buyers as well as developers would really have a choice, and then the feedback mechanism might work after a while. But at this point--and presumably (unfortunately) for much longer--Google is going to continue to impose a similar app tax and restrictions on app developers as Apple.

At any rate, there is a substantial problem here with switching costs (the double arrow on the left side), which also go beyond the photocopier situation because photocopier customers will replace a device, but smartphone OS users mostly buy their next phone with the same OS.

On the right side of the above chart, a thick black line indicates that either mobile app store (Apple's App Store and Google's Play Store) are walled gardens. There is no meaningful level of substitutability. You may be able to buy a digital item or content on one platform and use or consume it on another, but the App Store doesn't sell Android apps and the Google Play Store doesn't offer iOS apps.

Epic told the Ninth Circuit that its Kodak case is stronger than Kodak itself, and I agree. But Apple obviously tries to muddy the water, and certainly succeeded in confusing the district judge. Also, the judge imposed hard requirements for the aftermarket that simply aren't indispensable under the law, and which Epic now has to convince the Ninth Circuit to consider legally erroneous. I'll discuss them all further below. One of the implicit requirements she wrongly established is that the aftermarket cannot be a two-sided market (like the Amex market).

But in the mobile app store context, the aftermarket simply is a two-sided market with app stores matching developers and users (click on the image to enlarge):

If we (re)focus on what the Supreme Court really cared about it in Kodak, the fact that the aftermarket is two-sided is not irreconcilable with a single-brand market definition. If anything, it even strengthens the case. As Judge Rogers heard when she quizzed Tim Cook, Apple's CEO doesn't even get reports on developer satisfaction. So Apple's abusive behavior vis-à-vis developers only affects end users (who in turn might buy Android smartphones) if developers reduce their commitment to developing iOS apps. with a billion-plus people (which are presumably part of the 1.2 billion richest people on the planet) using iOS, that's not an option for developers. That's why Apple gets away with its conduct, with ever more restrictions, with doing damage to nascent product categories like NFT apps, with ads on individual app pages (another way of taxing developers), and so forth.

The fact that the app distribution business is a two-sided market even further insulates Apple from a potential backlash in the foremarket.

Before we discuss the wrongly imposed requirements on Epic in the aftermarket context, let me show you just one more chart. Android as a whole is actually even a three-sided market as Google intermediates between device makers, developers, and end users (click on the image to enlarge):

Google makes direct dealings between developers and device makers unattractive by limiting the appeal of device makers' own app stores. But developers wouldn't make Android devices if there weren't all those Android apps made by third-party developers. (Oherwise Windows Phone would have succeeded.)

The European Commission's Google Android decision and the affirmance of its largest part by the EU General Court correctly analyzed all three sides of that market and the choices they had (no alternative to device makers in the licensable mobile OS market; end users are locked in; developers have no choice but to develop for Android).

Unreasonable explicit and implicit aftermarket requirements

The district judge took extreme positions on what Epic would have to prove with respect to the proposed aftermarket being dissociated from the foremarket because she saw some other cases in which other courts (no matter if out of circuit anyway) applied Kodak to particular fact patterns and discussed ways in which an antitrust plaintiff could prove foremarket-aftermarket dissociation--but didn't say (and especially the Supreme Court and the Ninth Circuit never said) that those were absolute requirements.

Explicit requirement of customers' total unawareness: While it's obvious that end users weren't even aware of the app tax until Fortnite was ejected from the App Store in the summer of 2020, the district judge essentially criticized Epic for not having shown that iOS users are unaware of the App Store being the exclusive way to download iOS apps. But as Epic rightly notes in its reply brief, "Kodak does not require that consumers lack all knowledge of an alleged aftermarket monopolist’s conduct, just that they lack sufficient knowledge to adequately assess the full consequences of their actions when making purchasing decisions in the foremarket."

Explicit requirement of policy change: Total unawareness is obviously the case when a company changes its aftermarket terms after a cohort of customers made their purchasing decisions. But that doesn't make it a minimum requirement. Even one of the cases referenced by the district court's judgment, the Third Circuit opinion in Avaya v. Telecom Labs et al., doesn't establish a hard requirement of a policy change having occurred:

"In evaluating the evidence in Harrison Aire, we cautioned that, although '[o]ne important consideration is

whether a unilateral change in aftermarket policy exploits locked-in customers,' [...] “an ‘aftermarket policy change’ is not the sine qua non of a Kodak claim,” [...] Other factors to consider include [...]"

In fact, Judge YGR herself correctly focused on competition in the primary market being dissociated from conditions in the aftermarket when she denied in part a motion to dismiss in Ward v. Apple. I've read that entire decision, and in that case there were no misconceptions. Maybe some people would disagree with parts of it, but it was all perfectly logical and also very well-written (as opposed to the sloppy Epic v. Apple Rule 52 order with almost 300 typos, similar errors, and serious stylistic issues).

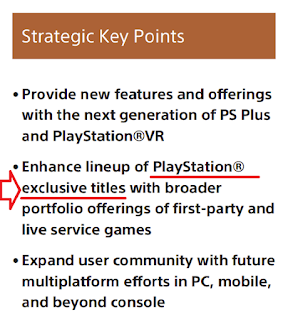

Implicit requirement of alleviating concerns over potential future cases involving other defendants: At the emergency-relief stage as well as in the Rule 52 order, Judge YGR faulted Epic for not explaining how a certain outcome of Epic v. Apple wouldn't also affect other walled gardens such as Sony's PlayStation. I've previously criticized the judge for that because this is too much of a good thing: yes, a sense of responsibility is an important trait in a judge; no, it's not a good idea to decide a case before a court based on facts and issues that are external to that case. It's utterly unreasonable to expect Epic--under the time constraints of its own case--to litigate hypothetical Epic v. Sony (with Sony being an Epic shareholder anyway) or Epic v. Microsoft (a company that is all for opening up app distribution and whose executives' testimony supported Epic) cases. The result was a wrong outcome in Epic v. Apple. The alternative would have been to decide Epic v. Apple without regard to those other cases, knowing that the likes of Sony and Microsoft could still defend themselves if they were sued by Epic or anybody else.

Concerns over spillover effects on other walled gardens could still have been raised at the appellate stage (where, again, Sony--as an Epic shareholder--is silent and Microsoft filed an amicus brief in support of Epic). It was always clear that the losing party would appeal.

Similarly, I believe it simply wasn't appropriate for the district court to rely on (partly misinterpreted) out-of-circuit precedent to argue that Kodak should be narrowed. Actually, today's digital markets come with network effects and switching costs that counsel in favor of identifying more--not fewer--single-brand markets. The Ninth Circuit found a single-brand market in Kodak, which the Supreme Court affirmed, and it then applied Kodak in Newcal.

Implicit requirement of aftermarket not being two-sided: As I already addressed further above, the two-sided nature of the mobile app distribution market doesn't make it ineligible for a Kodak aftermarket. The Supreme Court certainly didn't say anything like that in Amex--and while credit cards are used for the same transactions (for example, paying at a given restaurant), the Google Play Store doesn't offer iOS apps. Epic did recognize and address the two-sided nature of the App Store.

Unreasonably high hurdle for proving lock-in: Epic did present evidence that proves switching costs. Lock-in doesn't mean that no customer will switch: I remigrated from iOS to Android last year. The question is whether there's enough switching.

In this regard, the European Commission and the EU General Court took a pragmatic approach that makes a lot of sense. In Google Android, there was no question that users could theoretically change their default search engine, but the Commission and the EUGC focused on the fact that it doesn't happen sufficiently frequently to really make a difference.

Epic has pretty good chances of prevailing on market definition

I don't know the composition of the Ninth Circuit panel yet, but even if there were two or three "antitrust minimalists" on the panel, I believe Epic is more likely than not to prevail on market definition. I am 100% convinced--as an app developer and a smartphone user who has switched from Android to iOS and back--that Epic has a Kodak case. As a litigation watcher, I can see that Epic has very strong arguments for reversal. The district court got the law and some of the key facts wrong. It's telling that Apple even cites to a case decided by Justice Sotomayor back in 1997 when she was a district judge: Glob. Disc. Travel Servs., LLC v. Trans World Airlines, a case in which foremarket/aftermarket criteria played no role because there were alternative airlines selling tickets for certain routes (thus the proposed single-brand market definition in that case was just arbitrary; that case is closer to the ones in which U.S. courts rejected single-brand market definitions based on contracts, such as a claim brought by Domino's Pizza franchisees who complained after signing an agreement under which they had to buy all their ingredients from the defendant). Apple's brief mentioned Justice Sotomayor, but once the Ninth Circuit looks at the actual decision, it won't consider that citation relevant in the slightest.

If there's one part that I'm not totally sure whether it will work out in Epic's favor, that's the evidence of lock-in. There is a risk of the appeals court affirming the district judge's determination of a failure of proof. I'm not saying that it should. I's just the potentially weakest link of the chain. There's a risk of too much deference in that regard. What alleviates my concern is that virtually everyone knows what it's like to buy and use a smartphone. In a case involving products in a vertical market (like software for the administration of hospitals), an appeals court would find it harder to just overrule the district judge than when something as common and familiar as in Epic v. Apple is at stake.

Furthermore, the most impressive part of how the district judge handled the case was her deposition of Tim Cook, which made it so clear that any concessions Apple made (such as the 15% small business program) were not motivated by competition. That is, by the way, what I find so frustrating: Judge YGR actually had the situation all figured out in a certain way, but then didn't draw the necessary legal conclusions. She blamed Epic, its lawyers, and its experts for having overshot and for not having presented all of the evidence that might have been helpful. But she should nevertheless have ruled in Epic's favor, and the appeals court can easily overrule her now.

I would normally say Epic has an 80% chance of prevailing on the single-brand market definition (which would at minimum result in a remand), also because I believe the district court's judgment has so many flaws (even linguistic ones) that an appeals court can easily see there's something to be fixed there. But I do understand that courts are extra cautious about single-brand markets, and that's why my prediction is just that Epic is "more likely than not" to prevail on this one. If I had to give a number, I'd say 60%, but may adjust it once the panel is known.

Epic can win even under the "mobile gaming transactions" market definition, but I'm much less optimistic about its chances in that case, while I think Epic practically can't lose the case once the market has been defined correctly as a single-brand market.