On this last day of the first calendar quarter of 2023, it's worth recalling what an eventful quarter it was for the Microsoft-ActivisionBlizzard merger reviews--and time for a preview of the second quarter, which should be the home stretch.

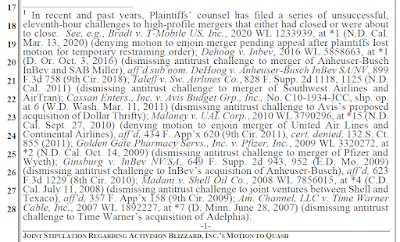

At the end of 2022, the transaction had been cleared--unconditionally--in four jurisdictions: Saudia Arabia, Brazil, Serbia, and--during the last week of the year--Chile. But the U.S. Federal Trade Commission had brought an (in-house) administrative complaint, and the European Commission as well as the UK Competition & Markets Authority (CMA) were investigating multiple potential concerns. Regulators in some others jurisdictions were apparently inclined to await the outcome in some other places before finalizing their own decisions. No agency made that cross-jurisdictional domino effect clearer than the Australian Competition & Consumer Commission (ACCC), which on February 2 announced that it was "engaging with overseas regulators" and that its own timeline would remain suspended for that reason.

As those merger reviews went into 2023, it looked like Sony's claim that Microsoft would remove Call of Duty from the PlayStation to make huge numbers of gamers switch to its Xbox console had quite some traction.

Surveys such as in Chile actually showed that most CoD fans would rather switch games than consoles, and that even among CoD gamers, Grand Theft Auto was potentially more popular--or at least it was clear that CoD wasn't a unique "must have" title as Sony claimed.

What made the traction Sony's theory seemingly had all the more astounding is that more competition among videogame consoles would actually be a good thing. Sony is the undisputed market leader. If one applies its own market definition, it is more than twice as big as the sole competitor (Xbox) on a worldwide basis, and about four times as big in Europe. In Japan, that market definition ("high-performance videogame consoles") would even make Sony a de facto monopolist.

I said "good thing" because consumers were never going to be deprived of choice. Microsoft made it clear all along that they wanted to bring more games to more gamers. While PlayStation gamers were never going to lose access to games as a result of the deal, ownership of Activision Blizzard obviously enables Microsoft to ensure that Sony couldn't strike exclusive deals designed to cement its leadership with Activision Blizzard. What Sony prefers is single-platform (PlayStation-only) titles. Alternatively, Sony will ensure that its users have some goodies such as making progress more rapidly ("double XP", which means "experience points"). It is, in fact, absolutely pro-competitive if more games are certain to be available on the Xbox--the PlayStation's only challenger based on Sony's own portrayal of market dynamics--on a "parity" basis.

It's simple economic logic that the dominant market leader can more easily strike exclusive deals with third parties and more profitably single-platform its first-party titles. The cost of foreclosing a minority platform is far lower than that of withdrawing or withholding a title from the platform on which most console gamers play. Game makers look at this not only from a revenue point of view but also take word-of-mouth and multiplayer dynamics into account: a game that is exclusive to the dominant platform can still be recommended by people to many of their friends, and friends can play together. Not so when a game is exclusive to a minority platform.

Sony's theory should have been rejected all along. But some regulators did not want to take this lightly, given that there is widespread concern over the power of "Big Tech." They wanted to take a closer look, and to set the stage for a potential agreement on remedies. It's also fair to say that competition authorities have so far had relatively little interaction with the games business (as a result--and unintended consequence--of Sony's vocal complaints, that may change going forward).

Sometimes things have to get worse before they get better. After the European Commission's Statement of Objections (SO) in late January and the UK CMA's publication in early February of its provisional findings, many observers were concerned that the transaction could be blocked--especially in the UK, where it is more difficult than in other major Western jurisdictions to have that kind of decision overturned by a court of law.

So, by the middle of this first quarter, one could have been led to think that the deal was at a high risk of being blocked. I was a bit of an outlier when I actually saw a silver lining in the CMA's remedies notice.

The second half of this quarter, however, delivered good news for the deal in multiple ways:

Right before the EU merger hearing, Microsoft announced the finalization of an agreement with console maker Nintendo.

After the Brussels hearing, a cloud gaming agreement with Nvidia, a company that was not an outright complainant over the deal but which had raised potential concerns, was announced. Once those concerns were addressed through successful negotiations, Nvidia threw its weight behind the transaction. On the basis of those two agreements alone, Microsoft was in a position to say that CoD would be brought to 150 million more devices. Consumer benefit rather than consumer harm. And let's not forget that Valve (known for Steam) said they didn't even need a contract with Microsoft because they could rely on a commitment.

Agreements with cloud gaming companies Boosteroid and Ubitus (which powers other companies' services) followed. Also, the CEO of Epic Games welcomed Microsoft's mobile app store plans, which will challenge the smartphone gatekeepers but can only come to fruition with a critical mass of apps, which is where Activision Blizzard King (and by far not only the King part) is indispensable. In light of all of those developments, I wrote that the focus of the merger debate had shifted "from concerns to constructive solutions and procompetitive effects".

In this regard, one must take into account that Microsoft has not only concluded several agreements with third parties but is prepared to do more of this, even on a basis that regulators could enforce if necessary (but won't have to because those commitments would be "self-executing").

The most important development, however, was that both the European Commission (based on what was reported about Microsoft's remedy proposals) and the UK CMA, which amended its provisional findings, abandoned the console market theory of harm. It's now just about cloud gaming, and that's where three players of different sizes have already determined that a contractual access guarantee works for them.

With the Japan Fair Trade Commission's announcement earlier this week, a fifth competition authority cleared the transaction:

The JFTC deserves respect for staying in the mainstream of global #antitrust enforcement, which is more than the U.S. FTC can say at the moment, regrettably.

— Florian Mueller (@FOSSpatents) March 28, 2023

Last month I commented very favorably on the JFTC's work to rein in digital #gatekeepers: https://t.co/YkOxamvWnxThe fact that United States District Judge Jacqueline Scott Corley granted Microsoft's motion to dismiss a so-called gamers' (actually lawyers') lawsuit is also interesting, though the class-action law firms behind that case won't give up until they exhaust all appeals or get paid, so they will refile (which appears to be taking them longer than they thought).

There was no bad news per se for the deal during the second half of the quarter. China's SAMR went into Phase 3, but there is no reason to assume that this is more than a delay. Chinese game makers like Tencent are in favor.

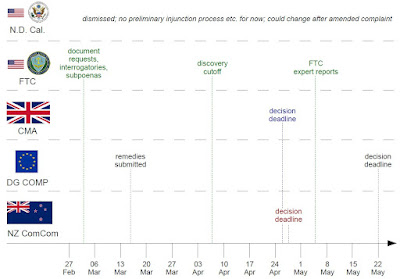

So what's next? The UK CMA expects to keep its schedule, which requires a decision on April 26. The European Commission has submitted Microsoft's proposed remedies to a market test, with MLex reporting that Sony and Google are (unsurprisingly) still unhappy but the European Games Developer Federation is in favor. The EC's deadline is May 22.

If there's clearance from the CMA in April and from the EC in May, the focus in June will shift to the U.S., where the FTC would have to seek a preliminary injunction in order to prevent the deal from closing. Statements keep coming out of the current U.S. administration that they have to take their chances in court to avoid underenforcement, but this merger doesn't have any of the ingredients of a case that would likely move the goal posts in the agencies' favor. It's not a good story to protect a market leader after eight--and by the time of a potential FTC PI motion--10 or more antitrust authorities have rejected that console market theory of harm, or to claim that the deal must be blocked because of the nascent cloud gaming market when the proposed remedy has in fact already been validated (not just tested in the form of questionnaires) by Nvidia, Boosteroid, Ubitus, and possibly others to come. It's just not the vehicle that the FTC needs for its strategic purposes.

UK in April, EU in May, U.S. in late May to early June--that could be the timetable for the second calendar quarter.