The website of the European Commission's Directorate-General for Competition (DG COMP) now lists the $68.7 billion Microsoft-ActivisionBlizzard merger under case number M.10646. According to the regulatory agency's website, formal notification was given today. Those who have previously been involved with (or closely tracking) EU merger reviews know that informal talks between the Commission and the parties to such a deal start a lot earlier than that.

In accordance with EU rules (Council Regulation 139/2004), the provisional deadline for a Phase 1 decision has been set for November 8, 2022. What the Commission has to decide at that point is whether to grant fast-track clearance or enter into a full-blown review (Phase 2) that could take several more months. Roughly in the middle of Phase 2, the Commission has to decide whether to hand down a Statement of Objections (SO), which is a preliminary ruling against which a notifying party can defend itself in writing and at a potential hearing. The process can terminate at any of those junctures, or anytime in between. DG COMP rarely blocks deals. It typically seeks commitments (sometimes more and sometimes less formal) to address any potential concerns.

In the U.S., the merger review process is already in the equivalent of EU Phase 2, as it is in the UK, where I was thoroughly disappointed to read a decision by the Competition & Markets Authority (CMA) that got even some basic facts and mechanics of the games industry wrong. After that decision, Microsoft had an eight-day deadline to offer commitments, which apparently didn't happen, so Phase 2 was opened in the UK.

Decisions in Australia and New Zealand have been postponed. Saudi Arabia granted fast-track clearance.

The only known complainant is Sony, the undisputed market leader in consoles (and the only platform operator to have more restrictive policies in some respects than Apple). Seriously, if Sony wasn't an Epic Games shareholder, it's fairly possible that Epic would have brought antitrust charges against the PlayStation company even before suing Apple. During the Epic v. Apple trial, some Epic-internal emails were shown that suggest at least some people at Epic were at some point even more concerned about Sony's policies than about Epic's. Now, Sony argues that Activision's Call of Duty is a must-have game for the PlayStation to continue to succeed--but it seems to hold a patent on that view because the public redacted versions of various other submissions to Brazilian antitrust authority CADE indicated that there would still be healthy competition in the games business.

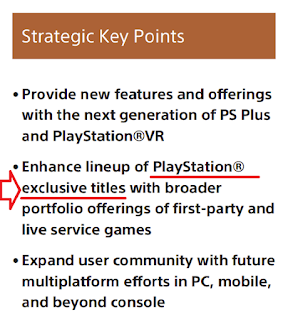

I'd like to highlight something I found in Sony's 2022 Corporate Report. They emphasize exclusives (click on the image to enlarge):

Apparently they're projecting their own predilection for exclusive titles onto Microsoft, a company that has a clear multi-platform track record (case in point: Minecraft).

Microsoft's public statements emphasize choice. There's now a web page dedicated to the transaction, which links to earlier statements such as one on app store governance.

The notion of a merger being delayed or in Sony's wet dreams even blocked just because it suits a market leader (PlayStation is #1) frankly turns competition law on its head.

I don't see any deal-specific issues here. It's a big deal in terms of transaction volume, but not a "big deal" from a competition point of view (as many industry players' Brazilian submissions show).

There has undoubtedly been underenforcement with respect to mergers. Just this week I pointed to Antitrust Assistant Attorney General Jonathan Kanter's testimony before the United States Senate. He vowed to take merger control more seriously. Looking at transactions that got cleared and substantially reduced competition, such as Facebook-WhatsApp, I can see where he and other competition enforcers around the world are coming from. As a consumer, I can see such problems in various areas (such as U.S. hotel chains). But the mistakes of the past cannot be corrected by going from one extreme (underenforcement) to the other (overenforcement). There must be justice in each case.

Merger control is indeed an important regulatory function. But as I wrote in the headline, merits must matter. If a deal is big, or one of the deal parties is a Big Tech company, that means the deal deserves a closer look, but doesn't represent, in and of itself, a credible theory of harm.